By Rowan McPhee

Physiotherapist at Life Ready Physio + Pilates Scarborough.

According to Athletics Australia, it is estimated that approximately 3 million Australians are running recreationally and that there has been a 57.8% increase in running participation in the last 10 years. Running has numerous physical and mental health benefits1 and is popular due to its low cost, versatility and convenience. Unfortunately running is also associated with a high prevalence of injury (up to 80%)2 and a large percentage of these are associated with overuse3.

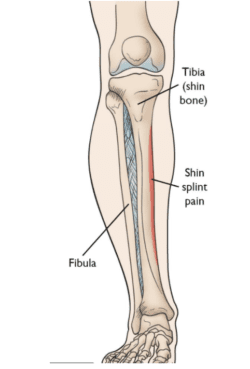

‘Shin Splints’, formally known as Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome (MTSS), is one of the most common forms of injury in the runner and thought to account for up to 20% of all running related injuries4. It is characterised by pain and tenderness along the lower insider border of the shin, often aggravated by impact exercise5. The pain is caused by inflammation of the periosteum (the thin lining that attaches muscle to bone) and in most cases, underlying micro-trauma to the cortical (outer) bone6. It is for this reason that the majority of runners will require a period of off-loading and a graded return to running program as those who try to ‘push through’ may be at risk of a continued and worsening symptoms. There is even debate as to whether MTSS is a precursor to tibial stress fracture7.

Known risk factors for ‘shin splints’ include increased BMI and over-pronation (inward rolling of the foot)8. For this reason, physiotherapists may advise on initial weight-loss through low impact exercise (such as swimming or cycling) and the prescription of appropriate motion control footwear or orthotics before commencing a graded return to running program. Although continued research is needed, physiotherapists also recommend combination of calf stretching and strength work targeting the calf, quadriceps and gluteals (see some examples below). The micro-trauma to the inside of the tibia (shin bone) is thought to be brought about by a ‘bowing’ effect on the tibia6 during impact and these forces can be attenuated by the calf complex and the external rotators of the hip (gluteals).

Ideally, the runner should be able to hop for at least 30 seconds on either leg, pain-free, before commencing a graded return to running program.

For further information on over-coming running related injury, contact our team to book an individualised assessment.

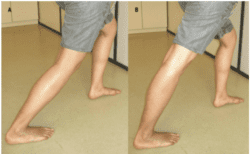

Gastroc stretch: lean forward against a wall with your back leg straight and both feet facing directly forward. Lunge forward with your front leg and keep your back heel in contact with the ground. Feel the stretch through the upper calf of your back leg. Hold for 30 seconds, rest for 30 seconds and repeat twice on both sides. Perform twice daily.

Soleus stretch: set up as per the stretch above but this time allow your back knee to bend a little. Keep the back heel in contact with the floor and lunge even further forward with your front leg. You should feel the stretch in the lower calf of your back leg this time. Hold for 30 seconds, rest for 30 seconds and repeat twice on both sides. Perform twice daily.

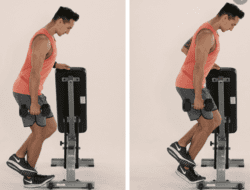

Bent knee calf raise: Although you can also perform this exercise with a straight knee, the lower calf muscle (soleus) works harder in this bent knee position (see above) and is the main shock-absorber/force producer in sub-maximal running.

Begin with the ball of your foot on a step and your knee slightly bent. Keeping the knee bent at around 30 degrees, rise up on to your tip toes keeping most of your pressure through your big toe. Come up for the count of 3 seconds and down for the count of 3 seconds.

Try to aim for 15 repetitions and perform 3 sets (with 1 minute rest between sets). Perform 2-3 times per week. As you progress, increase the challenge by adding weight and reducing your repetitions.

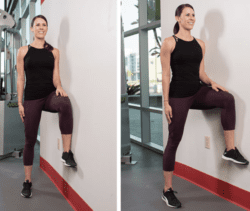

Wall Glute: Stand next to a wall and bring the leg closest to the wall up into a marching position (as shown above). Keeping your tail tucked under and hips level, gently press into the wall with your outer thigh, remaining strong through your standing leg. Feel your standing gluteal begin to work and hold for 20 seconds. Rest for 20 seconds and repeat 5 times. Perform the exercise 2-3 times per week on both sides.

References

- Lee D.C., Brellenthin A., Thompson P., Sui X., Lee I.M., Lavie C. (2017). Running as a Key Lifestyle Medicine for Longevity. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. Jun-Jul; 60 (1): 45-55

- Van Gent R.N., Siem D., van Middelkoop M., van Os A.G., Bierma-Zeinstra S.M., Koes B.W. (2007). Incidence and determinants of lower extremity running injuries in long distance runners: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. Aug; 41 (8): 469-80

- Van der Worp H., Vrielink J.W., Bredeweg S.W. (2016). Do Runners who Suffer Injuries have Higher Vertical Ground Reaction Forces than those who remain Injury-Free? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br J Sports Med. Apr; 50(8): 450-7

- Lopes A.D., Hespanhol L.C., Yeung S., Costa L. (2012) What are the main running-related musculoskeletal injuries? A Systematic Review. Sports Med. Oct 1; 42 (10): 891-905

- Winters M., Esks M., Weir A., Moen M.H., Backx F.J.G., Bakker E.W. P. (2013) Treatment of Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 43:1315-1333

- Franklyn M. & Oakes B. (2015) Aetiology and Mechanisms of Injury in Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome: Current and Future Development. World Journal of Orthopaedics. Sept 18; 6(8): 577-589

- Fredericson M., Bergman A.G., Hoffman K.K., Dillingham M.S. (1995) Tibial Stress Reaction in Runners. Correlation of Clinical Symptoms and Scintigraphy with new Magnetic Resonance Imaging Grading System. Am J Sports Med. 23: 472-481

- Winklemann Z.K., Anderson D., Games K.E., Eberman L. (2016) Risk Factors for Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome in Active Individuals: An Evidence Based Review. Journal of Athletic Training. 51 (12): 1049-1052